by Charles Reade

THERE are nobs in the world, and there are snobs.

I regret to say I belong to the latter department.

There are men that roll through life, like a fine new red ball going across Mr. Lord's cricket-ground on a sunshiny day; there is another sort that have to rough it in general, above all, to fight tooth and nail for the quartern-loaf, not always win the battle; I am one of this lot.

One comfort, folk are beginning to take an interest in us. I see nobs of the first water looking with a fatherly eye into affairs; our leaden taxes and feather incomes; our fifteen per cent, on undeniable security, when the rich pay but three and a half; our privations and vexations; our dirt and distresses; and one day a literary gent, that knows my horrible story, assured me that my ups and down would entertain the nobility, gentry, and commonalty of these realms.

"Instead of grumbling to me," says he, "print your troubles, and I promise you all the world will read them, laugh at them."

"No doubt, sir," said I rather ironical; "all the world is at leisure for that."

"Why, look at the signs of the times," says he; "can't you see workmen are up? So take us while we are in the humour, and that is now. We shall not always be for squeezing honey out of weeds, shall we?" "Not likely, sir," says I. Says he, "How nice it will be to growl wholesale to a hundred thousand of your countrymen (which they do love a bit of a growl) instead of growling retail to a small family that has got hardened to you!" And there he had me; for I am an Englishman, and proud of it, and attached to all the national habits, except delirium tremens. In short, what with him inflaming my dormant conceit, and me thinking, "Well, I can but say my say, and then relapse into befitting silence," I did one day lay down the gage and take up the pen, in spite of my wife's sorrowful looks.

She says nothing, but you may see she does not believe in the new tool, and that is cheerful and inspiriting to a beginner.

However, there is a something that gives me more confidence than all my literary friend says about "workmen being up in the literary world," and that is, that I am not the hero of my own story.

Small as I sit here behind my wife's crockery and my own fiddles, in this thundering hole, Wardour Street, I was for many years connected with one of the most celebrated females of modern times. Her adventures run side by side with mine; she is the bit of romance that colours my humble life, and my safest excuse for intruding on the public.

FATHER and mother lived in King Street, Soho. He was a fiddle-maker, and taught me the A B C of that science at odd times; for I had a regular education, and a very good one, at a school in West Street. This part of my life was as smooth as glass; my troubles did not begin till I was thirteen. At that age my mother died, and then I found out what she had been to me; that was the first and the worst grief. The next I thought bad enough. Coming in from school one day about nine months after her death, I found a woman sitting by the fire opposite father.

I came to a stand in the middle of the floor, with two eyes like saucers staring at the pair, so my father introduced me.

"This is your new mother. Anne, this is John."

"Come and kiss me, John," says the lady. Instead of which, John stood stock-still, and burst out roaring and crying, without the least leaving off staring, which, to be sure, was a cheerful, encouraging reception for a lady just come into the family. I roared pretty hard for about ten seconds, then stopped dead short, and says I, with a sudden calm, the more awful for the storm that had raged before, "I'll go and tell Mr. Paley;" and out I marched.

Mr. Paley was a little, hump-backed tailor with the heart of a dove and the spirit of a lion or two. I made his acquaintance through pitching into two boys that were queering his protuberances all down Princes Street, Soho--a kind of low humour he detested--and he had taken quite a fancy to me. We were hand and glove, the old man and me.

I ran to Paley and told him what had befallen upon the house. He was not struck all of a heap, as I thought he would be; and he showed me it was legal, of which I had not an idea, and his advice was, "Put a good face on it, or the house will soon be too hot to hold you, boy."

He was right. I don't know whether it was my fault or hers, or both's, but we could never mix. I had seen another face by that fireside and heard another voice in the house that seemed to me a deal more melodious than hers, and the house did become hotter, and the inmates' looks colder, than agreeable; so one day I asked my father to settle me in some other house not less than a mile from King Street, Soho. He and stepmother jumped at the offer, and apprenticed me to Mr. Dawes. Here I learned more mysteries of guitar-making, violin-making, &c., &c., and lived in tolerable comfort nearly four years. There was a ripple on the water, though. My master had a brother, a thick-set, heavy fellow, that used to bully my master, especially when he was groggy, and less able to take his own part. My master being a good fellow, I used to side with him, and this brought me a skinful of sore bones more than once, I can tell you. But one night, after some months of peace, I heard a terrible scrimmage, and running down into the shop-parlour, I found Dawes junior pegging into Dawes senior no allowance, and him crying blue murder.

I was now an able-bodied youth between sixteen and seventeen years of age, and having a little score of my own with the attacking party, I opened quite silent and business-like with a one, two, and knocked him into a corner flat perpendicular. He was dumfoundered for a moment, but the next he came out like a bull at me. I stepped on one side and met him with a blow on the side of the temple and knocked him flat horizontal; and when he offered to rise I shook my fist at him, and threatened him he should come to grief if he dared to move.

At this he went on quite a different lay; he lay still and feigned dissolution with considerable skill, to frighten us; and I can't say I felt easy at all; but my master, who took cheerful views of everything in his cups, got the enemy's tumbler of brandy and water, and, with hiccups and absurd smiles and a teaspoon, deposited the contents gradually on the various parts of his body.

"Lez revive 'm!" said he.

This was low life to come to pass in a respectable tradesman's back-parlour. But when grog comes in at the door good manners walk to the window, ready to take leave if requested. Where there is drink there is always degradation of some sort or degree; put that in your tumblers and sip it.

After this no more battles. The lowly apprentice's humble efforts (pugilistic) restored peace to his master's family.

Six months of calm industry now rolled over, and then I got into trouble by my own fault.

Looking back upon the various fancies and opinions and crotchets that have passed through my head at one time or another, I find that, between the years of seventeen and twenty-four, a strange notion beset me; it was this, that women are all angels.

For this chimera I now began to suffer, and continued to at intervals till the error was rooted out--with their assistance.

There were two women in my master's house, his sister, aged twenty-four, and his cook, aged thirty-seven. With both these I fell ardently in love; and so, with my sentiments, should have with six, had the house held half-a-dozen. Unluckily my affections were not accompanied with the discretion so ticklish a situation called for. The ladies found one another out, and I fell a victim to the virtuous indignation that fired three bosoms.

The cook, in virtuous indignation that an apprentice should woo his master's sister, told my master.

The young lady, in virtuous indig. that a boy should make a fool of "that old woman," told my master, who, unluckily for me, was now the quondam Dawes junior; Dawes senior having retired from the active business and turned sleeping and drinking partner.

My master, whose v. i. was the strongest of the three, since it was him I had leathered, took me to Bow Street, made his complaint, and forced me to cancel my indentures; the cook, with tears, packed up my Sunday suit; the young lady opened her bedroom door three inches and shut it with a don't-come-anigh-me slam; and I drifted out to London with eighteen-pence and my tools.

On looking back on this incident of my life, I have a regret, a poignant one; it is, that some good Christian did not give me a devillish good hiding into the bargain then and there.

I did not feel quite strong enough in the spirits to go where I was sure to be blown up; so I skirted King Street and entered the Seven Dials, and went to Mr. Paley and confessed my sins.

How differently the same thing is seen by different eyes! All the morning I had been called a young villain, first by one, then by another, till at last I began to see it: Mr. Paley viewed me in the light of martyr, and I remember I fell into his views on the spot.

Paley was a man that had his little theory about women, and it differed from my juvenile one.

He held that women are at bottom the seducers, men the seduced. "The men court the women, I grant you; but so it is the fish that runs after the bait," said he. "The women draw back? Yes; and so does the angler draw back the bait when the fish are shy, don't he? And then the silly gudgeons misunderstand the move, and make a rush at it, and get hooked--like you."

Holding such vile sentiments, he shifted all the blame off my shoulders; he turned to and abused the whole gang, as he called the family in Litchfield Street I had just left, instead of reading me the lesson for the day which he ought, and I should have listened to from him--perhaps.

"Now then, don't hang your head like that," shouted the spunky little fellow, "snivelling and whimpering at your time of life! We are going to have a jolly good supper, you and I; that is what we are going to do; and you shall sleep here. My daughter is at school; you shall have her room. I am in good work--thirty shillings a week; that is plenty for three, Lucy and you and me" (himself last). "Your father isn't worth a bone button, and your mother isn't worth the shank to it. I'm your father, and your mother into the bargain, for want of a better. You live with me, and snap your fingers at Dawes and all his crew--ha, ha--a fine loss, to be sure--the boy is a fool--cooks and coquettes and fiddle-touters, rubbish not worth picking up out of a gutter--they be d----d!"

And so I was installed in Miss Paley's apartment, Seven Dials; and nothing would have made my adopted parent happier than for me to put my hands in my pockets and live upon goose and cabbage. But downright laziness was never my character. I went round to all the fiddle-shops and offered, as bold as brass, to make a violin, a tenor, or a bass, and bring it home. Most of them looked shy at me, for it was necessary to trust me with the wood, and to lend me one or two of the higher class of tools, such as a turning-saw and a jointing-plane.

At last I came to Mr. Dodd in Berners Street. Here my father's name stood me in stead. Mr. Dodd risked his wood and the needful tools, and in eight days I brought him, with conceit and trepidation mixed in equal part, a violin, which I had sometimes feared it would frighten him, and sometimes hoped it would charm him. He took it up, gave it one twirl round,

satisfied himself it was a fiddle, good, bad, or indifferent, put it in the window along with the rest, and paid for it as he would for a penny roll. I timidly proposed to make another for him; he grunted a consent, which it did not seem to me a rapturous one.

Mr. Metzler also ventured to give me work of this kind. For some months I wrought hard all day, and amused myself with my companions all the evening, selecting my pals from the following classes: small actors, showmen, pedestrians, and clever discontented mechanics. One lot I never would have at any price, and that was the stupid ones, that could only booze, and could not tell me anything I did not know about pleasure, business, and life.

This was a bright existence, so it came to a full stop.

At one and the same time Miss Paley came home, and the fiddle-trade took one of those chills all fancy trades are subject to.

No work--no lodging without paying for it--no wherewithal.

JOHN BEARD, a friend of mine, was a painter and grainer. His art was to imitate oak, maple, walnut, satin-wood, &c., &c., upon vulgar deal, beech, or what not.

This business works thus: first a coat of oil-colour is put on with a brush, and this colour imitates what may be called the background of the wood that is aimed at; on this oil-background the champ, the fibre, the grain and figure, and all the incidents of the superior wood, are imitated by various maneuvers in water-colours, or rather in beer-colours, for beer is the approved medium. A coat of varnish over all gives a look of unity to the work.

Beard was out of employ; so was I: bitter against London; so was I. He sounded me about trying the country, and I agreed; and this was the first step of my many travels.

We started the next day, he with his brushes and a few colours and one or two thin panels painted by way of advertisement; and I with hope, inexperience, and threepence. On the road we spent this and his fivepence, and entered the town of Brentford towards nightfall as empty as drums and as hungry as wolves.

What was to be done? After a long discussion we agreed to go to the Mayor of the town and tell him our case, and offer to paint his street-door in the morning, if he would save our lives for the night.

We went to the Mayor. Luckily for us, he had risen from nothing, as we were going to do; and so he knew exactly what we meant when we looked up in his face and laid our hands on our sausage-grinders. He gave us eighteenpence and an order on a lodging-house, and put bounds to our gratitude by making us promise to let his street-door alone. We thanked him from our hearts, supped, and went to bed, and agreed the country (as we two cockneys called Brentford) was chock-full of good fellows.

The next day up early in the morning, and away to Hounslow. Here Beard sought work all through the town, and just when we were in despair he got one door. We dined and slept on this door, but we could not sup off it; we had twopence over, though, for the morning, and walked on a penny roll each to Maidenhead.

Here, as we entered the town, we passed a little house with the door painted oak, and a brass-plate announcing a plumber and glazier and house-painter. Beard pulled up before this door in sorrowful contempt. "Now look here, John," says he; "here is a fellow living among the woods, and you would swear he never saw an oak-plank in his life to look at his work."

Before so very long we came to another specimen; this was maple, and farther from Nature than a lawyer from heaven, as the saying is. "There, that will do," says Beard. "I'll tell you what it is, we must try a different move. It is no use looking for work; folks will only employ their own tradesmen. We must teach the professors of the art at so much a panel."

"Will they stomach that?" said I.

"I think they will, as we are strangers and from London. You go and see whether there is a fiddle to be doctored in the town, and meet me again in the market-place at twelve o'clock."

I did meet him, and forlorn enough I was; my trade had broke down in Maidenhead--not a job of any sort.

"Come to the public-house," was his first word. That sounded well, I thought.

We sat down to bread and cheese and beer, and he told his tale.

It seems he went into a shop, told the master he was a painter and grainer from a great establishment in London, and was in the habit of travelling and instructing provincial artists in the business. The man was a pompous sort of a customer, and told Beard he knew the business as well as he did, better belike.

Beard answered, "Then you are the only one here that does; for I've been all through the town, and anything wider from the mark than their oak and maple I never saw." Then he quietly took down his panels and spread them out, and looking out sharp, he noticed a sudden change come over the man's face.

"Well," says the man, "we reckon ourselves pretty good at it in this town. However, I shouldn't mind seeing how you London chaps do it. What do you charge for a specimen?"

"My charge is two shillings a panel. What wood should you like to gain a notion of?" said Beard, as dry as a chip.

"Well--satin-wood."

Beard painted a panel of satin-wood before his eyes; and of course it was done with great ease, and on a better system than had reached Maidenhead up to that time. "Now," says Beard, "I must go to dinner."

"Well, come back again, my lad," says the man, "and we will go in for something else." So Beard took his two shillings and met me as aforesaid.

After dinner he asked for a private room. "A private room!" said I. "Hadn't you better order our horse and gig out and go and call on the rector?"

"None of your chaff," says he.

When we got into the room he opened the business.

"Your trade is no good; you must take to mine."

"What! teach painters how to paint, when I don't know a stroke myself!"

"Why not? You've only got it to learn: they have got to unlearn all they know; that is the only long process about it. I'll teach you in five minutes," says he. "Look here." He then imitated oak before me, and made me do it. He corrected my first attempt; the second satisfied him. We then went on to maple, and so through all the woods he could mimic. He then returned to his customer, and I hunted in another part of the town; and before nightfall I actually gave three lessons to two professors. It is amazing, but true, that I, who had been learning ten minutes, taught men who had been all their lives at it--in the country.

One was so pleased with his tutor that he gave me a pint of beer besides my fee. I thought he was poking fun when he first offered it me.

Beard and I met again triumphant. We had a rousing supper and a good bed, and the next day started for Henley, where we both did a small stroke of business; and on to Reading for the night.

Our goal was Bristol. Beard had friends there. But as we zig-zagged for the sake of the towns, we were three weeks walking to that city; but we reached it at last, having disseminated the science of graining in many cities, and got good clothes and money in return.

At Bristol we parted. He found regular employment the first day, and I visited the fiddle-shops and offered my services. At most I was refused; at one or two I got trifling jobs; but at last I went to the right one. The master agreed with me for piece-work on a large scale, and the terms were such that, by working quick and very steady, I could make about twenty-five shillings a week. At this I kept two years, and might have longer, no doubt; but my employer's niece came to live with him.

She was a woman; and my theory being in full career at this date, mutual ardour followed, and I asked her hand of her uncle, and instead of that he gave me what the Turkish ladies get for the same offence--the sack. Off to London again, and the money I had saved by my industry just landed me in the Seven Dials and sixpence over.

I went to Paley, crestfallen as usual. He heard my story, complimented me on my energy, industry, and talent, regretted the existence of women, and inveighed against her character and results.

We went that evening to private theatricals in Berwick Street, and there I fell in with an acquaintance in the firework line. On hearing my case, he told me I had just fallen from the skies in time; his employer wanted a fresh hand.

The very next day behold me grinding and sifting and ramming powder at Somers Town, and at it ten months.

My evenings, when I was not undoing my own work to show its brilliancy, were often spent in private theatricals.

I hear a row made just now about a dramatic school. "We have no dramatic schools," is the cry. Well, in the day I speak of there were several. Why, I belonged to two. We never brought to light an actor; but we succeeded so far as to ruin more than one had who had brains enough to make a tradesman, till we heated those brains and they boiled all away.

The way we destroyed youth was this. Of course nobody would pay a shilling at the door to see us running wild among Shakspere's lines like pigs broken into a garden; so the expenses fell upon the actors; and they paid according to the value of the part each played. Richard the Third cost a puppy two pounds, Richmond fifteen shillings, and so on; so that with us, as in the big world, dignity went by wealth, not merit. I remember this made me sore at the time. Still, there are two sides to everything. They say poverty urges men to crime; mine saved me from it. If I could have afforded, I would have murdered one or two characters that have lived with good reputation from Queen Bess to Queen Victoria; but as I couldn't afford it, others that could did it for me.

Well, in return for his cash, Richard, or Hamlet, or Othello commanded tickets in proportion; for the tickets were only gratuitous to the spectators.

Consequently at night each important actor played not only to a most merciful audience, but a large band of devoted, friendly spirits in it, who came not to judge him, but express to carry him through triumphant--like an election. Now, when a vain, ignorant chap hears a lot of hands clapping, he has not the sense to say to himself, "Paid for!" No, it is applause; and applause stamps his own secret opinion of himself. He was off his balance before, and now he tumbles heel over tip into the notion that he is a genius; throws his commercial prospects after the two pounds that went in Richard or Beverley, and crosses Waterloo Bridge spouting--

"A fico for the shop and poplins base!

Counter, avaunt! I on his southern bank

Will fire the Thames."

Noodle thus singing goes over the water. But they won't have him at the Surrey or the Vic., so he takes to the country; and while his money lasts, and he can pay the mismanager of a small theatre, he gets leave to play with Richard and Hamlet. But when the money is gone and he wants to be paid for Richard & Co., they laugh at him, and put him in his right place, and that is a utility, and perhaps ends a "super.;" when, if he had not been a coxcomb, he might have sold ribbon like a man to his dying day.

We, and our dramatic schools, ruined more than one or two of this sort by means of his vanity in my young days.

My poverty saved me. The conceit was here in vast abundance, but not the funds to intoxicate myself with such choice liquors as Hamlet & Co. Nothing above old Gobbo (five shillings) ever fell to my lot and by my talent.

When I had made and let off fireworks for a few months, I thought I could make more as a rocket-master than a rocket-man. I had saved a pound or two. Most of my friends dissuaded me from the attempt; but Paley said, "Let him alone now; don't keep him down; he is born to rise. I'll risk a pound on him." So, by dint of several small loans, I got the materials and made a set of fireworks myself, and agreed with the keeper of some tea-gardens at Hampstead for the spot.

At the appointed time, attended by a trusty band of friends, I put them up; and when I had taken a tolerable sum at the door, I let them all off.

But they did not all profit by the permission. Some went, but others whose supposed destination was the sky, soared about as high as a house, then returned and forgot their wild nature, and performed the office of our household fires upon the clothes of my visitors; and some faithful spirits, like old domestics, would not leave their master at any price--would not take their discharge. Then there was a row, and I should have been mauled, but my guards rallied round me and brought me off with whole bones, and marched back to London with me, quizzing me and drinking at my expense. The publican refused to give me my promised fee, and my loss by ambition was twenty-eight shillings, and my reputation--if you could call that a loss.

Was not I quizzed up and down the Seven Dials! Paley alone contrived to stand out in my favour. "Nonsense, a first attempt," said he. "They mostly fail. Don't you give in for those fools. I'll tell you a story. There was a chap in prison--I forget his name. He lived in the old times, a few hundred years ago--I can't justly say how many. He had failed--at something or other--I don't know how many times--and there he was. Well, Jack, one day he notices a spider climbing up a thundering great slippery stone in the wall. She got a little way, then down she fell. Up again and tries it on again--down again. 'Aha,' says the man, 'you will never do it.' But the spider was game. She got six falls; but, by George! the seventh trial she got up. So the gentleman says, 'A man ought to have as much heart as a spider; I won't give in till the seventh trial.' Bless you, long before the seventh he carried all before him, and got to be king of England, or something."

"King of England!" said I; "that was a move upwards out of the stone jug."

"Well," said Paley the hopeful, "you can't be king of England, but you may be the fire-king--he, he!--if you are true to powder. How much money do you want to try again?"

I was nettled at my failure, and fired by Paley and his spider, I scraped together a few pounds once more, and advertised a display of fireworks for a certain Monday night.

On the Sunday afternoon Paley and I happened to walk on the Hampstead Road, and near the "Adam and Eve" we fell in with an announcement of fireworks. On the bill appeared in enormous letters the following:--

"NO CONNECTION WITH THE DISGRACEFUL EXHIBITION THAT TOOK PLACE LAST FRIDAY WEEK!!"

Paley was in a towering passion. "Look here, John," says he. "But never you mind; it won't be here long, for I'll tear it down in about half a moment."

"No, you must not do that," said I, a little nervous.

"Why not, you poor-spirited muff?" shouts the little fellow. "Let me alone; let me get at it. What are you holding me for?"

"No! no! no! Well, then----"

"Well, then, what?"

"Well, then, it is mine."

"What is yours?"

"That advertisement."

"How can it be yours when it insults you?"

"Oh, business before vanity."

"Well, I am blest! Here's a go. Look here now;" and he began to split his sides laughing; but all of a sudden he turned awful grave. "You will rise, my lad; this is genuine talent. They might as well try to keep a balloon down." In short, my friend, who was as honest as the day in his own sayings and doings, admired this bit of rascality in me, and augured the happiest results.

That district of London which is called the Seven Dials was now divided into two great parties: one augured for me a brilliant success next day, the other a dead failure. The latter party numbered many names unknown to fame; the former consisted of Paley. I was neuter, distrusting not my merits, but what I called my luck.

On Monday afternoon I was busy putting out the fireworks, nailing them to their posts, &c. Towards evening it began to rain so heavily that they had to be taken in and the whole thing given up; it was postponed to Thursday.

On Thursday night we had a good assembly; the sum taken at the doors exceeded my expectation. I had my misgivings on account of the rain that had fallen on my kickshaws Monday evening; so I began with those articles I had taken in first out of the rain. They went off splendidly, and my personal friends were astounded. But soon my poverty began to tell; instead of having many hands to save the fireworks from wet, I had been alone, and of course much time had been lost in getting them under cover. We began now to get along the damp lot, and science was lost in chance; some would and some wouldn't, and the people began to goose me.

A rocket or two that fizzed themselves out without rising a foot inflamed their angry passions; so I announced two fiery pigeons.

The fiery pigeon is a pretty firework enough; it is of the nature of a rocket, but being on a string, it travels backwards and forwards between two termini, to which the string is fixed. When there are two strings and two pigeons, the fiery wings race one another across the ground, and charm the gazing throng. One of my termini was a tree at the extremity of the gardens. Up this tree I mounted in my shirt-sleeves with my birds. The people surrounded the tree and were dead silent. I could see their final verdict and my fate hung on these pigeons. I placed them, and with a beating heart lighted their matches. To my horror, one did not move. I might as well have tried to explode green sticks. The other started, and went off with great resolution and accompanying cheers towards the opposite side. But midway it suddenly stopped and the cheers with it. It did not come to an end all at once, but the fire oozed gradually out of it like water. A howl of derision was hurled up into the tree at me; but, worse than that, looking down I saw in the moonlight a hundred stern faces with eyes like red-hot emeralds, in which I read my fate. They were waiting for me to come down, like terriers for a rat in a trap, and I felt by the look of them that they would kill me, or near it. I crept along a bough the end of which cleared the wall and overhung the road. I determined to break my neck sooner than fall into the hands of an insulted public. An impatient orange whizzed by my ear, and an apple knocked my hat out of the premises. I crouched and clung.

Luckily I was on an ash-bough, long, tapering, and tough; it bent with me like a rainbow. A stick or two now whizzed past my ear, and it began to hail fruit. I held on like grim death till the road was within six feet of me, and then dropped and ran off home, like a dog with a kettle at his tail. Meantime a rush was made to the gate to cut me off, but it was too late. The garden meandered, and my executioners, when they got to the outside, saw nothing but a flitting spectre--me in my shirt-sleeves making for the Seven Dials.

Mr. and Miss Paley were seated by their fire, and, as I afterwards learned, Paley was recommending her to me for a husband, and explaining to her at some length why I was sure to rise in the world, when a figure in shirt-sleeves, begrimed with gunpowder and no hat, burst into the room, and shrank without a word into the corner by the fire.

Miss Paley looked up, and then began to look down and snigger. Her father stared at me, and after a while I could see him set his teeth and nerve his obstinate old heart for the coming struggle.

"Well, how did it happen?" said he at last. "Where is your coat?"

I told him the whole story.

Miss Paley had her hand to her mouth all the time, afraid to give vent to the feelings proper to the occasion because of her father.

"Now answer me one question. Have you got their money?" says Paley.

"Yes, I have got their money, for that matter."

"Well, then, what need you care? You are all right; and if they had gone off they would have been all over by now just the same. He wants his supper, Lucy. Give us something hot, to make us forget our squibs and crackers, or we shall die of a broken heart, all us poor fainting souls. Such a calamity! The rain wetted them through; that is all; You couldn't fight against the elements, could you? Lay the cloth, girl."

"But, Mr. Paley," whined I, "they have got my new coat, and you may be sure they have torn it limb from jacket."

"Have they?" cried he. "Well, that is a comfort any way. Your new coat, eh? Lucy, it hung on the boy's back like an old sack. Do you see this bit of cloth? I shall make you a Sunday coat with this, and then you'll sell. Fetch a quart to-night, girl, instead of a pint; the fire-king is going to do us the honour. Che-er up!!"

IT was now time that Miss Paley should suffer the penalty of her sex. She was a comely, good-humoured, and sensible girl. We used often to walk out together on Sundays, and very friendly we were. I used to tell her she was the flower of her sex, and she used to laugh at that. One Sunday I spoke more plainly, and laid my heart, my thirteen shillings, the fruit of my last imposture on the public, and my various arts at her feet, out walking.

A proposal of this sort, if I may trust the stories I read, produces thrilling effects. If agreeable, the ladies either refuse in order to torment themselves, which act of virtue justifies them, they think, in tormenting the man they love; or else they show their rapturous assent by bursting out crying or by fainting away, or their lips turning cold, and other signs proper to a disordered stomach. If it is to be "no," they are almost as much cut up about it, and say no like yes, which has the happy result of leaving him hope and prolonging his pain. Miss Paley did quite different. She blushed a little and smiled archly, and said, "Now, John, you and I are good friends, and I like you very much; and I will walk with you and laugh with you as much as you like; but I have been engaged these two years to Charles Hook, and I love him, John."

"Do you, Lucy?"

"Yes," under her breath a bit.

"Oh!"

"So if we are to be friends you must not put that question to me again, John. What do you say? We are to be friends, are we not?" and she put out her hand.

"Yes, Lucy."

"And, John, you need not go for to tell my father; what is the use vexing him? He has got a notion, but it will pass away in time."

I consented, of course, and Lucy and I were friends.

Mr. Paley somehow suspected which way his daughter's heart turned, and not long after a neighbour told me he heard him quizzing her unmerciful for her bad judgment. As for harshness or tyranny, that was not under his skin, as the saying is. He wound up with telling her that John was a man safe to rise.

"I hope he may, father, I am sure," says Lucy.

"Well, and can't you see he is the man for you?"

"No, father, I can't see that--he, he!"

I DON'T think I have been penniless not a dozen times in my life. When I get down to twopence or threepence, which is very frequent indeed, something is apt to turn up and raise me to silver once more, and there I stick. But about this time I lay out of work a long time, and was reduced to the lowest ebb. In this condition a friend of mine took me to the "Harp" in Little Russell Street to meet Mr. Webb, the manager of a strolling company. Mr. Webb was beating London for recruits to complete his company, which lay at Bishop-Stortford, but which, owing to desertions, was not numerous enough to massacre five-act plays. I instantly offered to go as carpenter and scene-shifter. To this he demurred; he was provided with them already. He wanted actors. To this I objected. Not that I cared to what sort of work I turned my hand, but in these companies a carpenter is paid for his day's work according to his agreement, but the actors are remunerated by a share in the night's profits, and the profits are often written in the following figures, £0, 0s. 0d.

However, Mr. Webb was firm; he had no carpenter's place to offer me, so I was obliged to lower my pretensions. I agreed, then, to be an actor. I was cast as Father Philip in the "Iron Chest" next evening, my share of the profits be one-eighth. I borrowed a shilling, and my friend Johnstone and I walked all the way to Bishop-Stortford. We played the "Iron Chest," and divided the profits. Hitherto I had been in the mechanical arts; this was my first step into the fine ones. Father Philip's share of the "Chest" was 2 and a half d.

Now this might be a just remuneration for the performance. I almost think it was; but it left the walk--thirty miles--not accounted for.

The next night I was cast in "Jerry Sneak." I had no objection to the part; only, under existing circumstances, the place to play it seemed to me to be the road to London, not the boards of Bishop-Stortford; so I sneaked off towards the Seven Dials. Johnstone, though cast for the hero, was of Jerry's mind, and sneaked away along with him.

We had made but twelve miles when the manager and a constable came up with us. Those were peremptory days; they offered us our choice of the fine arts again or prison. After a natural hesitation we chose the arts, and were driven back to them like sheep. Night's profits 5d. In the morning the whole company dissolved away like a snowball. Johnstone and I had a meagre breakfast, and walked on it twenty-six miles. He was a stout fellow--shone in brigands; he encouraged and helped me along, but at last I could go no farther.

My slighter frame was quite worn out with hunger and fatigue. "Leave me," I said; "perhaps some charitable hand will aid me; and if not, why then I shall die; and I don't care if I do, for I have lost all hope."

"Nonsense," cried the fine fellow. "I'll carry you home on my back sooner than leave you. Die? That is a word a man should never say. Come, courage; only four miles more."

No; I could not move from the spot. I was what I believe seldom really happens to any man, dead beat, body and soul.

I sank down on a heap of stones. Johnstone sat down beside me.

The sun was just setting. It was a bad look out. Starving people to lie out on stones all night. A man can stand cold and he can fight with hunger; but put those two together and life is soon exhausted.

At last a rumble was heard, and presently an empty coal-waggon came up. A coal-heaver sat on the shaft, and another walked by the side. Johnstone went to meet them. They stopped. I saw him pointing to me, and talking earnestly.

The men came up to me; they took hold of me and shot me into the cart like a hundredweight of coal. "Why, he is starving with cold," said one of them, and he flung half-a-dozen empty sacks over me, and on we went. At the first public the waggon stopped, and soon one of my new friends, with a cheerful voice, brought a pewter flagon of porter to me. I sipped it. "Don't be afraid of it," cried he. "Down with it; it is meat and drink, that is." And indeed so I found it. It was a heavenly, solid liquid to me; it was "stout" by name and "stout" by nature.

These good fellows, whom men do right to call black diamonds, carried me safe into the Strand, and thence being now quite my own man again, I reached the Seven Dials. Paley was in bed. He came down directly in his nightgown, and lighted a fire and pulled a piece of cold beef out of the cupboard, and cheered me as usual, but in a fatherly way this time; and of course at my age I was soon all right again, and going to take the world by storm tomorrow morning. He left me for a while and went upstairs. Presently he came down again.

"Your bed is ready, John."

"Why," said I, "you have not three rooms."

"Lucy is on a visit," said he; then he paused. "Stop a bit; I'll warm your bed."

He took me upstairs to my old room and warmed the bed. I, like a thoughtless young fool, rolled into it, half-gone with sleep, and never woke till ten next morning.

I don't know what the reader will think of me when I tell him that the old man had turned Lucy out of her room into his own and sat all night by the fire that I might lie soft after my troubles. Ah! he was a bit of steel. And have you left me, and can I share no more sorrow or joy with you in this world! Eh dear! it makes me misty to think of the old man, after all these years.

I USED often to repair and doctor a violin for a gent whom I shall call Chaplin; he played in the orchestra of the Adelphi Theatre. Mr. Chaplin was not only a customer, but a friend; he saw how badly off I was, and had a great desire to serve me. Now it so happened that Mr. Yates, the manager, was going to give an entertainment he called his "At Homes," and this took but a small orchestra, of which Mr. Chaplin was to be the leader; so he was allowed to engage the other instruments, and he actually proposed to me to be a second violin.

I stared at him. "How can I do that?"

"Why, I often hear you try a violin."

"Yes, and I always play the same notes; perhaps you have observed that too?"

"I notice it is always a slow movement--eh? Never mind; this is the only thing I can think of to serve you. You must strum out something; it will be a good thing for you, you know."

"Well," said I, "if Mr. Yates will promise to sing nothing faster than 'Je-ru-sa-lem, my hap-py home,' I'll accompany him."

No, he would not be laughed out of it; he was determined to put money in my pocket, and would take no denial. "Next Monday you will have the goodness to meet me at the theatre at six o'clock with your fiddle. Play how you like; play inaudible, for what I care; but play and draw your weekly salary you must and shall."

"Play inaudible"--these words sank to the very bottom of me. "Play inaudible."

I fell into a brown study; it lasted three days and three nights. Finally, to my good patron's great content, I consented to come up to the scratch; and Monday night I had the hardihood to present myself in the music-room of the Adelphi. My violin was a ringing one; I tuned up the loudest of them all, and Mr. Chaplin's eye rested on me with an approving glance.

Time was called. We played an overture, and accompanied Mr. Yates in his recitatives and songs, and performed pieces and airs between the acts, &c. The leader's eye often fell on me, and when it did, he saw the most conscientious workman of the crew ploughing every note with singular care and diligence.

In this same little orchestra was James Bates, another favourite of Mr. Chaplin and an experienced fiddler.

This young man was a great chum of mine. He was a fine, honest young fellow, but of rather a saturnine temper; he was not movable to mirth at any price. He would play without a smile to a new pantomime--stuck there all night like Solomon cut in black marble with a white choker, as solemn as a tomb, with hundreds laughing all around.

Once or twice while we were at work I saw Mr. Chaplin look at Bates, knowing we two were chums, and whenever he did it seems the young one bit his lips and turned as red as a beetroot. After the lights were out Mr. Chaplin congratulated me before Bates. "There, you see, it is not so very hard. Why, hang me if you did not saw away as well as the best!!!" At these words Bates gave a sort of yell and ran home. Mr. Chaplin looked after him with surprise. "There's some devil's delight up between you two," said he. "I shall find it out."

Next night, in the tuning-room, my fiddle was so resonant it attracted attention, and one or two asked leave to try it. "Why not?" said I.

During work Mr. Chaplin had one eye on me and one on Bates, and caught the perspiration running down my face, and him simpering for the first time in the history of the Adelphi.

"What has come over Jem Bates?" said Mr. Chaplin to me. "The lad is all changed; you have put some of your late gunpowder into him. There is something up between you two." After the play he got us together, and he looked Bates in the face and just said to him, "Eh?"

At this wholesale interrogatory Bates laid hold of himself tight. "No, Mr. Chaplin, sir, I can't; it will kill me when it does come out of me."

"When what comes out? You young rascals, if you don't both of you tell me I'll break my fiddle over Bates, and Jack shall mend it free of expense, gratis for nothing; that is how I'll serve mutineers. Come, out with it."

"Tell him, John," said Bates demurely.

"No," said I; "tell him yourself if you think it will gratify him." I had my doubts.

"Well," said Bates, "it is ungrateful to keep you out of it, sir; so--he! he! --I'll tell you, sir--this second-violin has two bows in his violin-case."

"Well, stupid, what is commoner than that for a fiddler?"

"But this is not a fiddler," squeaked Bates; "he's only a bower. Oh! oh! oh!"

"Only a bower?"

"No! Oh! oh! I shall die; it will kill me." I gave a sort of ghastly grin myself.

"You unconscionable scoundrels!" shouted Mr. Chaplin. "There, look at this, Bates; he is at it again--a fellow that the very clown could never raise a laugh out of; and now I see him all night smirking and grinning and looking down like a jackdaw that has got his claw on a thimble. If you don't speak out I'll knock your two tormenting skulls together till they roll off down the gutter side by side, chuckling and giggling all day and all night." At this direful, mysterious threat Bates composed himself. "The power is all out of my body, sir, so now I can tell you."

He then, in faint tones, gave this explanation, which my guilty looks confirmed. "One of his bows is resined, sir; that one is the tuner. I don't know whether you have observed, but he tunes rather louder than any two of us. Oh dear! it is coming again."

"Don't be a fool now. Yes, I have noticed that."

"The other bow, Mr. Chaplin, sir, the other bow is soaped, well soaped, sir, for orchestral use. Ugh! Ugh!"

"Oh, the varmint!"

Bates continued. "You take a look at him--you see him fingering and bowing like mad--but as for sound, you know what a greasy bow is?"

"Of course I do. I don't wonder at your laughing--ha, ha, ha! Oh, the thief!--when I think of his diligent face and him shaking his right wrist like Viotti."

"Mind your pockets, though; he knows too much."

It was now my turn to speak. "I am glad you like the idea, sir," said I, "for it comes from you."

"How can you say that?"

"What did you tell me to do?"

"I didn't tell you to do that. I don't remember what I told him, Bates--not to the letter."

"Told me to play inaudible!!!"

"Well, I never!" said Mr. Chaplin.

"Those were your words, sir; they did not fall to the ground, you see."

My position in this orchestra and the situations that arose out of it were meat and drink to my two friends. With the gentry, whose lives are a succession of amusements, a joke soon wears out, no doubt; but we poor fellows can't let one go cheap. How do we know how long it may be before Heaven sends us another? A joke falling among us is like a rat in a kennel of terriers.

At intricate passages the first-violin used to look at the tenor and then at me, and wink, and they both swelled with innocent enjoyment, till at last unknown powers of gaiety budded in Bates. With quizzing his friend he learned to take a jest; so much so that one night Mr. Yates being funnier than usual, if possible, a single horse-laugh suddenly exploded among the fiddles. This was Bates gone off all in a moment, after his trigger being pulled so many years to no purpose. Mr. Yates looked down with gratified surprise.

"Hallo! brains got in the orchestra. After that anything!"

But do you think it was fun to me all this? I declare I suffered the torture of the--you know what. I never felt safe a moment. I had placed myself next to an old fiddler who was deaf, but he somehow smelt at times that I was shirking, and then he used to cry, "Pull out, pull out; you don't pull out."

"How can you say so?" I used to reply, and then saw away like mad; when, so connected are the senses of sight and hearing apparently, the old fellow used to smile and be at peace. He saw me pull, and so he heard me pull out. Then sometimes friends of the other performers would be in the orchestra, and peep over me and say civil things, and I wish them further, civilities and all. But it is a fact that for two months I gesticulated in that orchestra without a soul finding out that I was not suiting the note to the action.

At last we broke up, to my great relief; but I did not leave the theatre. Mr. Widger, Mr. Yates's dresser, got me a place behind the scenes at nine shillings per week.

I used to dress Mr. Reeve and run for his brandies and waters, which kept me on the trot, and do odd jobs.

But I was now to make the acquaintance that coloured all my life, or the cream of it. My time was come to move in a wider circle of men and things, and really to do what so many fancy they have done--to see the world.

In the month of April 1828 Mr. Yates, theatrical manager, found his nightly receipts fall below his nightly expenses. In this situation a manager falls upon one of two things--a spectacle or a star. Mr. Yates preferred the latter, and went over to Paris and engaged Mademoiselle Djek.

Mademoiselle Djek was an elephant of great size and unparalleled sagacity. She had been for some time performing in a play at Franconi's, and created a great sensation in Paris.

Of her previous history little is known. But she was first landed from the East in England, and was shown about merely as an elephant by her proprietor, an Italian called Polito. The Frenchmen first found out her talent. Her present owner was a M. Huguet, and with him Mr. Yates treated. She joined the Adelphi company at a salary of £40 a week and her grub.

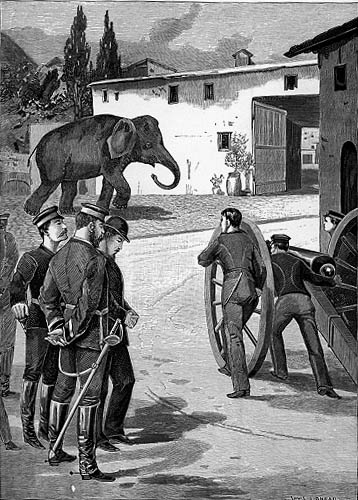

There was great expectation in the theatre for some days. The play in which she was to perform, "The Elephant of the King of Siam," was cast and rehearsed several times; a wooden house was built for her at the back of the stage; and one fine afternoon, sure enough, she arrived with all her train, one or two of each nation, viz., her owner, M. Huguet (French); her principal keeper, Tom Elliot (English); her subordinates, Bernard (French) and an Italian nicknamed Pippin. She arrived at the stage-door in Maiden Lane, and soon after the messenger was sent to Mr. Yates's house.

"Elephant's come, sir."

"Well, let them put her in the place built for her, and I'll come and see her."

"They can't do that, sir."

"Why not?"

"La bless you, sir! she might get her foot into the theatre, but how is her body to come through the stage-door? Why, she is almost as big as the house."

Down comes Mr. Yates, and there was the elephant standing all across Maiden Lane, all traffic interrupted except what could pass under her belly; and such a crowd, my eye!

Mr. Yates put his hands in his pockets and took a quiet look at the state of affairs.

"You must make a hole in the wall," said he.

Pickaxes went to work and made a hole, or rather a frightful chasm, in the theatre, and when it looked about two-thirds her size Elliot said "Stop!" He then gave her a sharp order, and the first specimen we saw of her cleverness was her doubling herself together and creeping in through that hole, bending her fore-knees, and afterwards rising and dragging her hind-legs horizontally, and so she disappeared like an enormous mole burrowing into the theatre.

Mademoiselle Djek's bills were posted all over the town, and everything done to make her take; and on the following Tuesday the theatre was pretty well filled by the public. The manager also took care to have a strong party in the pit. In short, she was nursed as other stars are upon their début.

Night came; all was anxiety behind the lights and expectation in front.

The green curtain drew up, and Mr. Yates walked on in black dress-coat and white kid gloves, like a private gentleman just landed out of a bandbox at the Queen's ball. He was the boy to talk to the public: soft sawder, dignified reproach, friendly intercourse--he had them all at his fingers'-ends. This time it was the easy tone of refined conversation upon the intelligent creature he was privileged to introduce to them. I remember his discourse as well as if it was yesterday.

"The elephant," said Mr. Yates, "is a marvel of Nature. We are now to have the pleasure of showing her to you as taking her place in art." Then he praised the wisdom and beneficence of creation. "Among the small animals, such as cats and men, there is to be found such a thing as spite, treachery ditto, and love of mischief, and even cruelty at odd times; but here is a creature with the power to pull down our houses about our ears like Samson, but a heart that will not let her hurt a fly. Properly to appreciate her moral character consider what a thing power is; see how it tries us, how often in history it has turned men to demons. The elephant," added he, "is the friend of man by choice, not by necessity or instinct; it is born as wild as a lion or buffalo, but the moment an opportunity arrives its kindred intelligence allies it to man, its only superior or equal in reasoning power. We are about," said Mr. Yates, "to present a play in which an elephant will act a part, and yet act but herself, for the intelligence and affectionate disposition she will display on these boards as an actress are merely her own private and domestic qualities. Not every one of us actors, gentlemen, can say as much."

Then there was a laugh, in which Mr. Yates joined. In short, Mr. Yates, who could play upon the public ear better than some fiddles (I name no names), made his débutante popular before ever she stepped upon the scene. He then bowed with intense gratitude to the audience for the attention they had honoured him with, retired to the prompter's side, and as he reached it the act-drop flew up and the play began. It commenced on two legs; the elephant did not come on until the second scene of the act.

The drama was a good specimen of its kind: it was a story of some interest and length and variety, and the writer had been sharp enough not to make the elephant too common in it; she came on only three or four times, and always at a nick of time, and to do good business, as theatricals say, i. e., for some important purpose in the story.

A king of Siam had lately died, and the elephant was seen taking her part in the funeral obsequies. She deposited his sceptre, &c., in the tomb of his fathers, and was seen no more in that act. The rightful heir to this throne was a young prince to whom the elephant belonged. An usurper opposed him, and a battle took place; the rightful heir was worsted and taken prisoner; the usurper condemned him to be thrown into the sea. In the next act this sentence was being executed; four men were discovered passing through a wood carrying no end of a box. Suddenly a terrific roar was heard; the men put down the box rather more carefully than they would in real life and fled, and the elephant walked on to the scene alone like any other actress. She smelt about the box, and presently tore it open with her proboscis, and there was her master, the rightful heir, but in a sad, exhausted state. When the good soul sees this what does she do but walk to the other side and tear down the bough of a fruit-tree and hand it to the sufferer: he sucked it, and it had the effect of stout on him--it made a man of him, and they marched away together, the elephant trumpeting to show her satisfaction.

In the next act the rightful heir's friends were discovered behind the bars of a prison at a height from the ground. The order for their execution arrived, and they were down upon their luck terribly. In marched the elephant, tore out the iron bars, and squeezed herself against the wall, half squatting in the shape of a triangle; so then the prisoners glided down her to the ground slantendicular one after another.

When the civil war had lasted long enough to sicken both sides, and enough widows and orphans had been made, the Siamese began to ask themselves, "But what is it all about?" The next thing was they said, "What asses we have been! Was there no other way of deciding between two men but bleeding the whole tribe?" Then they reflected, and said, "We are asses, that is clear; but we hear there is one animal in the nation that is not an ass; why, of course then she is the one to decide our dispute." Accordingly a grand assembly was held; the rival claimants were compelled to attend, and the elephant was led in. Then the high priest, or some such article, having first implored Heaven to speak through the quadruped, bade her decide according to justice. No sooner were the words out of his mouth than the elephant stretched out her proboscis, seized a little crown that glittered on the usurper's head, and waving it gracefully in the air, deposited it gently and carefully on the brows of the rightful heir. So then there was a rush made on the wrongful heir; he was taken out, guarded, and warned off the premises; the rightful heir mounted the throne and grinned and bowed all round, the elephant trumpeted, Siam hurrahed, Djek's party in the house echoed the sound, and down came the curtain in thunders of applause. Though the curtain was down the applause continued most vehemently, and after a while a cry arose at the back of the pit, "Elephant! Elephant!" That part of the audience that had paid at the door laughed at this, but their laughter turned to curiosity when, in answer to the cry, the curtain was raised and the stage discovered empty. Curiosity in turn gave way to surprise; for the elephant walked on from the third grooves alone and came slap down to the float. At this the astonished public literally roared at her. But how can I describe the effect, the amazement, when, in return for the compliment, the débutante slowly bent her knees and curtseyed twice to the British public, and then retired backwards as the curtain once more fell? People looked at one another, and seemed to need to read in their neighbours' eyes whether such a thing was real; and then followed that buzz which tells the knowing ones behind the curtain that the nail has gone home; that the theatre will be crammed to the ceiling to-morrow night, and perhaps for eighty nights after.

Mr. Yates fed Mademoiselle Djek with his own hand that night, crying, "Oh, you duck!"

The fortunes of the Adelphi rose from that hour--full houses without intermission.

Mr. Yates shortened his introductory address, and used to make it a brief, neat, and, I think, elegant eulogy of her gentleness and affectionate disposition; her talent "the public are here to judge for themselves," said Mr. Yates, and exit P. S.

A theatre is a little world, and Djek soon became the hero of ours. Everybody must have a passing peep at the star that was keeping the theatre open all summer and providing bread for a score or two of families connected with it. Of course a mind like mine was not among the least inquisitive. But her head-keeper, Tom Elliot, a surly fellow, repulsed our attempts to scrape acquaintance. "Mind your business, and I'll mind mine," was his chant. He seemed to be wonderfully jealous of her. He could not forbid Mr. Yates to visit her, as he did us, but he always insisted on being one of the party even then. He puzzled us. But the strongest impression he gave us was, that he was jealous of her; afraid she would get as fond of some others as of him, and so another man might be able to work her, and his own nose lose a joint, as the saying is. Later on we learned to put a different interpretation on his conduct. Pippin the Italian and Bernard the Frenchman used to serve her with straw and water, &c., but it was quite a different thing from Elliot. They were like a fine lady's grooms and running footmen, but Elliot was her body-servant, groom of the bed-chamber, or what not. He used always to sleep in the straw close to her; sometimes, when he was drunk, he would roll in between her legs, and if she had not been more careful of him than any other animal ever was (especially himself) she must have crushed him to death three nights in the week. Next to Elliot, but a long way below him, M. Huguet seemed her favourite. He used to come into her box and caress her, and feed her, and make much of her; but she never went on the stage without Elliot in sight, and in point of fact all she did upon our stage was done at a word of command given then and there, at the side, by this man and no other--going down to the float, curtseying and all.

Being mightily curious to know how he had gained such influence with her, I made several attempts to sound him, but drunk or sober he was equally unfathomable on this point.

I then endeavoured to slake my curiosity at No. 2. I made bold to ask M. Huguet how he had won her affections. The Frenchman was as communicative as the native was reserved; he broke plenty of English over me. It came to this, that the strongest feeling of an elephant was gratitude, and that he had worked on this for years; was always kind to her and seldom approached her without giving her lumps of sugar--carried a pocket full on purpose. This tallied with what I had heard and read of an elephant, still the problem remained, Why is she fonder still of this Tom Elliot, whose manner is not ingratiating, and who never speaks to her but in a harsh, severe voice?

She stood my friend any way. A good many new supers were engaged to play with her, and I was set over these--looked out their dresses and went on with them and her as a slave. Nine shillings a week for this was added to my other nine which I drew for dressing an actor or two of the higher class.

The more I was about her the more I felt that we were not at the bottom of this quadruped, nor even of her bipeds. There were gestures and glances and shrugs always passing to and fro among them.

One day, at the rehearsal of a farce, there was no Mr. Yates. Somebody inquired loudly for him.

"Hush!" says another; "haven't you heard?"

"No."

"You mustn't talk of it out of doors."

"No!"

"Half killed by the elephant this morning."

It seems he was feeding and coaxing her, as he had often done before, when all in a moment she laid hold of him with her trunk and gave him a squeeze. He lay in bed six weeks with it, and there was nobody to deliver her eulogy at night. Elliot was at the other end of the stage when the accident happened; he heard Mr. Yates cry out, and ran in, and the elephant let Mr. Yates go the moment she saw him.

We questioned Elliot. We might as well have cross-examined the Monument. Then I inquired of M. Huguet what this meant. That gentleman explained to me that Djek had miscalculated her strength; that she wanted to caress so kind a manager who was always feeding and courting her, and had embraced him too warmly.

The play went on and the elephant's reputation increased. But her popularity was destined to receive a shock as far as we little ones behind the curtain were concerned.

One day, while Pippin was spreading her straw, she knocked him down with her trunk, and pressing her tooth against him, bored two frightful holes in his skull, before Elliot could interfere. Pippin was carried to St. George's Hospital, and we began to look in one another's faces.

Pippin's situation was in the market.

One or two declined it. It came down to me; I reflected, and accepted it--another nine shillings; total, twenty-seven shillings.

That night two supers turned tail. An actress also, whose name I have forgotten, refused to go on with her. "I was not engaged to play with a brute," said this lady, "and I won't." Others went on as usual, but were not so sweet on it as before. The rightful heir lost all relish for his part, and above all, when his turn came to be preserved from harm by her, I used to hear him crying out of the box to Elliot, "Are you there? Are you sure you are there?" and when she tore open his box, Garrick never acted better than this one used to now; for, you see, his cue was to exhibit fear and exhaustion, and he did both to the life, because for the last five minutes he had been thinking, "Oh dear! oh dear! suppose she should do the foot business on my box, instead of the proboscis business."

These, however, were vain fears; she made no mistake before the public.

Nothing lasts for ever in this world, and the time came that she ceased to fill the house. Then Mr. Yates re-engaged her for the provinces, and having agreed with the country managers, sent her down to Bath and Bristol first. He had a good opinion of me, and asked me to go with her and watch his interests. I should not, certainly, have applied for the place, but it was not easy to say no to Mr. Yates, and I felt I owed him some reparation for the wrong I had done that great artist in accompanying his voice with my gestures.

In short, we started, Djek, Elliot, Bernard, I, and Pippin, on foot (he was just out of St. George's). Messrs. Huguet and Yates rolled in their carriage to meet us at the principal towns where we played.

As we could not afford to make her common, our walking was all night-work, and introduced me to a rough life.

The average of night weather is wetter and windier than day, and many a vile night we tramped through when wise men were abed; and we never knew for certain where we should pass the night, for it depended on Djek. She was so enormous that half the inns could not find us a place big enough for her. Our first evening stroll was to Bath and Bristol; thence we crossed to Dublin; thence we returned to Plymouth. We walked from Plymouth to Liverpool, playing with good success at all these places. At Liverpool she laid hold of Bernard, and would have settled his hash, but Elliot came between them.

That same afternoon in walks a young gentleman dressed in the height of Parisian fashion--glossy hat, satin tie, toursers puckered at the haunches--sprucer than any poor Englishman will be while the world lasts; and who was it but Mons. Bernard come to take leave. We endeavoured to dissuade him; he smiled and shook his head, treated us, flattered us, and showed us his preparations for France.

All that day and the next he sauntered about us, dressed like a gentleman, with his hands in his pockets and an ostentatious neglect of his late affectionate charge. Before he left he invited me to drink something at his expense, and was good enough to say I was what he most regretted leaving.

"Then why go?" said I.

"I will tell you, mon pauvre garçon," said Mons. Bernard. "We old hands have all got our orders to say she is a duck. Ah, you have found that out of yourself. Well now, as I done with her, I will tell you a part of her character, for I know her well. Once she injures you she can never forgive you. So long as she has never hurt you there's a fair chance she never will. I have been about her for years, and she never molested me till yesterday. But if she once attacks a man, that man's death-warrant is signed. I can't altogether account for it, but trust my experience it is so. I would have stayed with you all my life if she had not shown me my fate; but not now. Merci! I have a wife and two children in France. I have saved some out of her; I return to the bosom of my family, and if Pippin stays with her after the hint she gave him in London, why, you will see the death of Pippin, my lad, voilà tout; that is, if you don't go first. Qu'est que ça te fait à la fin? tu es garçon toi--buvons!"

The next day he left us, and left me sad for one. The quiet determination with which he acted upon positive experience of her was enough to make a man thoughtful. And then Bernard was the flower of us; he was the drop of mirth and gaiety in our iron cup. He was a pure, unadulterated Frenchman, and, to be just, where can you find anything so delightful as a Frenchman--of the right sort?

He fluttered home, singing--

"Les doux yeux de ma brunet--te,

Tout--e mignonett--e--tout--e gentillett--e,"

and left us all in black.

God bless you, my merry fellow! I hope you found your children healthy, and your brunette true, and your friends alive, and that the world is just to you, and smiles on you, as you do on it, and did on us.

From Liverpool we walked to Glasgow; from Glasgow to Edinburgh; and from Edinburgh, on a cold, starry midnight, we started for Newcastle.

In this interval of business let me paint you my companions, Pippin and Elliot. The reader is entitled to this, for there must have been something out of the common in their looks, since I was within an ace of being killed along of the Italian's face, and was imprisoned four days through the Englishman's mug.

The Italian, whom we know by the nickname of Pippin, was a man of immense stature and athletic mould. His face, once seen, would never be forgotten. His skin, almost as swarthy as Othello's, was set off by dazzling ivory teeth and lighted by two glorious large eyes, black as jet, brilliant as diamonds. The orbs of black lightning gleamed from beneath eyebrows that many a dandy would have bought for moustaches at a high valuation. A nose like a reaping-hook completed him--perch him on a tolerable-sized rock, and there you had a black eagle.

As if this was not enough, Pippin would always wear a conical hat, and had he but stepped upon the stage in "Massaniello," or the like, all the other brigands would have sunk down to rural police by the side of our man. But now comes the absurdity: his inside was not different from his out; it was the exact opposite. You might turn over twenty thousand bullet-heads and bolus-eyes before you could find one man so thoroughly harmless as this thundering brigand. He was just a pet, an universal pet of all the men and women that came near him. He had the disposition of' a dove and the heart of a hare. He was a lamb in wolf's clothing.

My next portrait is not so pleasing.

Some ten years before this, a fine, stout young English rustic entered the service of Mademoiselle Djek. He was a model for bone and muscle, and had two cheeks like roses. When he first went to Paris he was looked on as a curiosity there. People used to come to Djek's stable to see her and Elliot, the young English Samson. Just ten years after this young Elliot had got to be called "old Elliot." His face was not only pale, it was colourless; it was the face of a walking corpse. This came of ten years' brandy and brute. I have often asked people to guess the man's age, and they always guessed sixty, sixty-five, or seventy; oftenest the latter.

He was thirty-five, not a day more.

This man's mind had come down along with his body. He understood nothing but elephant; he seldom talked, and then nothing but elephant. He was an elephant-man. I will give you an instance, which I always thought curious.

An elephant, you may have observed, cannot stand quite The great weight of its head causes a nodding movement, which is perpetual when the creature stands erect. Well, this Tom Elliot, when he stood up, used always to have one foot advanced, and his eye half closed, and his head niddle-noddling like an elephant all the time; and with it all such a presence of brute and absence of soul in his mug, enough to give a thoughtful man some very queer ideas about man and beast.

My office in this trip was merely to contract for the elephant's food at the various places; but I was getting older and shrewder, and more designing than I used to be, and I was quite keen enough to see in this elephant the means of bettering my fortunes if I could but make friends with her. But how to do this? She was like a coquette: strange admirers welcome; but when you had courted her a while she got tired of you, and then nothing short of your demise satisfied her caprice. Her heart seemed inaccessible, except to this brute Elliot, and he, drunk or sober, guarded the secret of his fascination by some instinct; for reason he possessed in a very small degree.

I played the spy on quadruped and biped, and I found out the fact, but the reason beat me. I saw that she was more tenderly careful of him than a mother of her child. I saw him roll down stupid drunk under her belly, and I saw her lift first one foot and then the other, and draw them slowly and carefully back, trembling with fear lest she might make a mistake and hurt him.

But why she was a mother to him, and a stepmother to the rest of us, that I could not learn.

One day, between Plymouth and Liverpool, having left Elliot and her together, I happened to return, and I found the elephant alone and in a state of excitement, and looking in, I observed some blood upon the straw.

"His turn has come at last" was my first notion; but looking round, there was Elliot behind me.

"I was afraid she had tried it on with you," I said.

"Who?"

"The elephant."

Elliot's face was not generally expressive, but the look of silent scorn he gave me at the idea of the elephant attacking him was worth seeing. The brute knew something I did not know, and could not find out; and from this one piece of knowledge he looked down upon me with a sort of contempt that set all the Seven Dials blood on fire.

"I will bottom this," said I, "if I die for it."

My plan now was to feed Djek every day with my own hand, but never to go near her without Elliot at my very side and in front of the elephant.

This was my first step.

We were now drawing towards Newcastle, and had to lie at Morpeth, where we arrived late, and found Mr. Yates and M. Huguet, who had come out from Newcastle to meet us; and at this place I determined on a new move which I had long meditated.

Elliot, I reflected, always slept with the elephant. None of the other men had ever done this. Now might there not be some magic in this unbroken familiarity between the two animals?

Accordingly at Morpeth I pretended there was no bed vacant in the inn, and asked Elliot to let me lie beside him; he grunted an ungracious assent.

Not to overdo it at first, I got Elliot between me and Djek, so that, if she was offended at my intrusion, she must pass over her darling to resent it. We had tramped a good many miles, and were soon fast asleep.

About two in the morning I was awoke by a shout and a crunching, and felt myself dropping into the straw out of the elephant's mouth. She had stretched her proboscis over him, had taken me up so delicately that I felt nothing, and when Elliot shouted I was in her mouth; at his voice, that rang in my ears like the last trumpet, she dropped me like a hot potato. I rolled out of the straw giving tongue a good one, and ran out of the shed. I had no sooner got to the inn than I felt a sickening pain in my shoulder and fainted away.

Her huge tooth had gone into my shoulder like a wedge. It was myself I had heard being crunched.

They did what they could for me, and I soon came to. When I recovered my senses I was seized with vomiting; but at last all violent symptoms abated, and I began to suffer great pain in the injured part, and did suffer for six weeks.

And so I scraped clear. Somehow or other Elliot was not drunk, or nothing could have saved me; for a second wonder, he, who was a heavy sleeper, woke at the very slight noise she made eating me; a moment later and nothing could have saved me. I use too many words--suppose she had eaten me, what then?

They told Mr. Yates at breakfast, and he sent for me and advised me to lie quiet at Morpeth till the fever of the wound should be off me; but I refused. She was to start at ten, and I told him I should start with her.

Running from grim death like that I had left my shoes behind in the shed, and M. Huguet sent his servant Baptiste, an Italian, for them.

Mr. Yates then asked me for all the particulars, and whilst I was telling him and M. Huguet we heard a commotion in the street, and saw people running, and presently one of the waiters ran in and cried--

"The elephant has killed a man or near it."

Mr. Yates laughed and said--

"Not quite so bad as that; for here is the man."

"No, no!" cried the waiter; "it is not him; it is one of the foreigners."

Mr. Yates started up all trembling; he ran to the stable. I followed him as I was, and there we saw a sight to make our blood run cold. On the corn-bin lay poor Baptiste crushed into a mummy. How it happened there was no means of knowing; but, no doubt, while he was groping in the straw for my wretched shoes she struck him with her trunk, perhaps more than once. His breast-bones were broken to chips, and every time he breathed, which, by God's mercy, was not many minutes, the man's whole chest-frame puffed out like a bladder with the action of his lungs--it was too horrible to look at.

Elliot bad run at Baptiste's cry, but too late to save his life this time. He had drawn the man out of the straw as she was about to pound him to a jelly, and there the poor soul lay on the corn-bin, and by his side lay the things he had died for--two old shoes. Elliot had found them in the straw and put them there, of all places in the world.

By this time all Morpeth was out. They besieged the doors and vowed death to the elephant. M. Huguet became greatly alarmed; he could spare Baptiste, but he could not spare Djek. He got Mr. Yates to pacify the people. "Tell them something," said he.

"What on earth can I say for her over that man's bleeding body?" said Mr. Yates. "Curse her! would to God I had never seen her!"

"Tell them he mused her cruel," said M. Huguet. "I have brought her off with that before now."

Well, my sickness came on again, partly no doubt by the sight and the remorse, and I was got to bed, and lay there some days; so I did not see all that passed, but I heard some, and I know the rest by instinct now.

Half-an-hour after breakfast-time Baptiste died. On this the elephant was detained by the authorities, and a coroner's inquest was summoned, and sat in the shambles on the victim, with the butcheress looking on at the proceedings.

Pippin told me she took off a juryman's hat during the investigation, waved it triumphantly in the air, and placed it cleverly on her favourite's head--old Tom.

At this inquest two or three persons deposed on oath that the deceased had ill-used her more than once in France; in particular that he had run a pitchfork into her two years ago; that he had been remonstrated with, but in vain; unfortunately she had recognised him at once, and killed him out of revenge for past cruelty, or to save herself from fresh outrages.

This cooled the ardour against her. Some even took part with her against the man.

"Run a pitchfork into an elephant! Oh, for shame! No wonder she killed him at last. How good of her not to kill him then and there! What forbearance!--forgave it for two years, ye see."

There is a fixed opinion among men that an elephant is a good, kind creature; the opinion is fed by the proprietors of elephants, who must nurse the notion or lose their customers, and so a set tale is always ready to clear the guilty and criminate the sufferer, and this tale is greedily swallowed by the public. You will hear and read many such tales in the papers before you die. Every such tale is a lie.